Top Stories

Top Stories

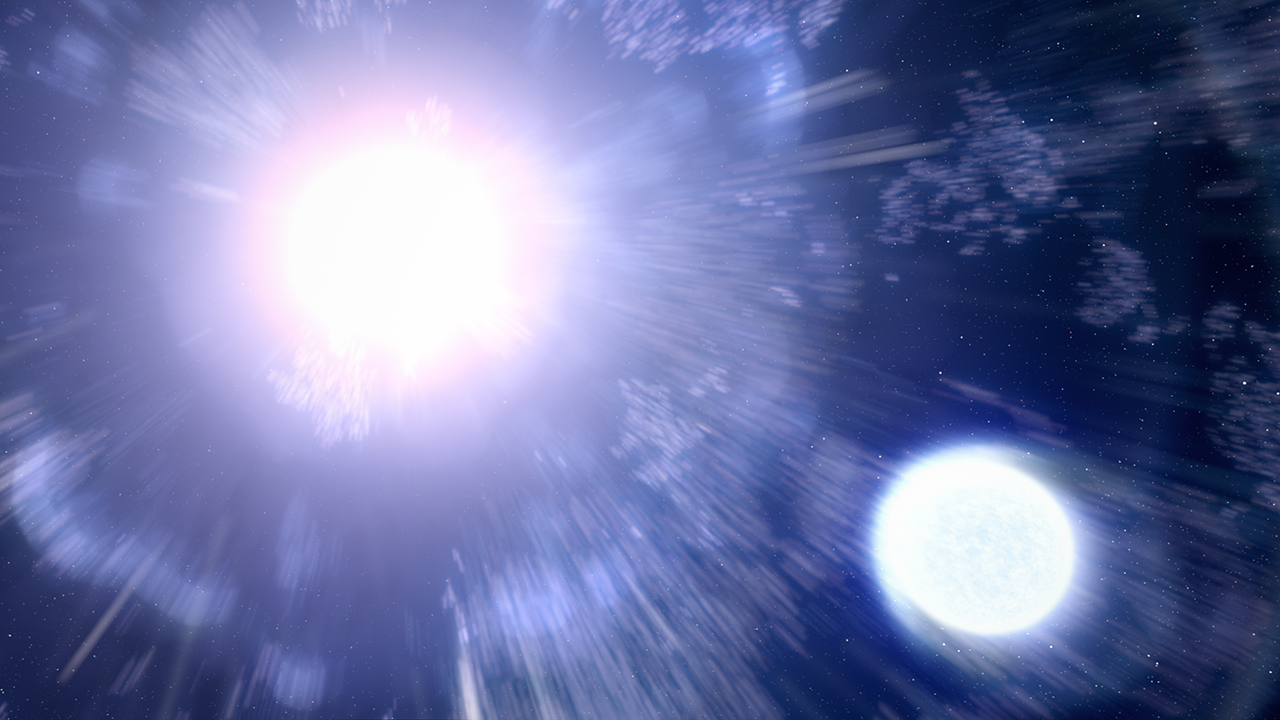

Some space radiation colliding with Earth has a dangerous beginning. Stargazers spotted destruction from a cosmic explosion blast possibly equipped for impacting out high-energy particles — or vast beams — that often besiege Earth. Their new discoveries connect shockwaves and destruction made by biting the dust stars to regular high-energy proton gas pedals in space, which are named PeVatrons. These fascinating inestimable gas pedals — which accept their name from their capacity to help the energies of particles to outrageous peta-electronvolt (PeV) levels — have never been indisputably recognized. A modest bunch of thought PeVatrons were at that point fingerprinted before this review, including one at the focal point of our Milky Way universe.

The examination group says their new find of a cosmic explosion blast's extras — a haze of material called G106.3+2.7 — could be the most encouraging up-and-comer yet. Related: What is a cosmic explosion? The destruction prowls 2,600 light-years from Earth, has a comet-shape and has a brilliant pulsar — a profoundly attractive pivoting neutron star — toward one side. Since neutron stars structure when stars go through gravitational breakdown, which likewise jump starts out cosmic explosions, there is valid justification for scientists to believe that the pulsar and the cosmic explosion destruction cloud were made by a similar fierce occasion. Utilizing NASA's Fermi Large Area Telescope, cosmologists detected a high-energy gamma-beam phosphorescence that suggests G106.3+2.7 might be equipped for the PeVatron-related accomplishment of shooting out particles at energies comparable to a million billion electronvolts — multiple times as perfect as energies created by the Large Hadron Collider , Earth's most remarkable atom smasher. "Scholars think the most elevated energy vast beam protons in the Milky Way arrive at a million billion electron volts or PeV energies," right hand teacher of material science at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, Ke Fang said in a NASA proclamation. (opens in new tab) "The exact idea of their sources, which we call PeVatrons, has been challenging to nail down." Scientists suspect the cosmic explosion destruction from dead stars speeds up particles to such high energies when charged particles are trapped by attractive fields around them. This interaction permits shockwaves from the cosmic explosion to buffet the caught particles over and over, expanding their energy each time. At long last, the particles are enthusiastic to the point that the cosmic explosion remains can't clutch them, and the particles escape into space at close light-speeds as vast beams. Following enormous beams back to cosmic explosion destruction has been troublesome in light of the fact that the protons that contain astronomical beams are electrically charged. Grandiose beams are along these lines inclined to dispersing while at the same time cooperating with attractive fields as they venture through space. Space experts, thusly, can only with significant effort tell from which bearing the beams are coming when they at long last arrive at our planet. Since the speed increase of protons to such high rates causes the emanation of gamma-beams, in any case, this high-energy light could be a decent intermediary for identifying the wellspring of grandiose beams. Related: Most Powerful Cosmic Rays Come from Galaxies Far, Far Away Both Fermi and the Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System (VERITAS) at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory, southern Arizona, distinguished gamma-beams from inside the tail of the cosmic explosion destruction of G106.3+2.7. Furthermore, different observatories have found incredibly high-energy photons coming from a similar region, showing this could for sure be a PeVatron.

"This item has been a wellspring of impressive interest for some time now, yet to crown it as a PeVatron, we needed to demonstrate it is speeding up protons," specialist Henrike Fleischhack of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said. "The catch is that electrons advanced to a couple hundred TeV can deliver a similar discharge. Presently, with the assistance of 12 years of Fermi information, we think we've presented the defense that G106.3+2.7 is to be sure a PeVatron." — Humans Really Are Made of Stardust, and a New Study Proves It — Supernovas May Seed the Universe with More Stardust Than Predicted — NASA's Stardust Mission: The Space Probe That Brought Stardust to Earth To dissect gamma-beams from the comet-molded cloud, the group needed to initially represent the pulsar — named J2229+6114 — radiating its own gamma-beams as it quickly turns. Since the high-energy light is just impacted towards Earth during half of the pulsar's rotational period, the analysts essentially disregarded gamma-beam discharges during this period. The tail of G106.3+2.7 seems to discharge not many gamma-beam photons with energies under 10 Giga-electronvolts (GeV); over this benchmark, the pulsar's impact was little. The absence of gamma-beams under 10 GeV additionally showed the recognized outflows were not brought about by the speeding up electrons. This tracking down drove the scientists to construe that the wellspring of some gamma-beams from G106.3+2.7 was without a doubt the speed increase of protons to PeV-level energies. "Up until this point, G106.3+2.7 is extraordinary, however it might end up being the most splendid individual from another populace of cosmic explosion remainders that produce gamma beams arriving at TeV energies," Fang said. "A greater amount of them might be uncovered through future perceptions by Fermi and extremely high-energy gamma-beam observatories." The group's discoveries are examined in a paper distributed in the August 10 release of the diary Physical Review Letters. (opens in new tab) Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab) .